My comments posted on Indian Express webpage over Praveen Swamy's article: Generations of avengers ....

Praveen Swamy is a senior Journalist with a one-track mind. Unlike an ideal journalist, who should be objective in his/her reporting or analysis, Swamy deals with so-called Jihadi terrorism. He has never bothered to go deeper into the psyche that drives people towards 'terrorism' or if this terrorism could be state policy to keep Muslims subdued. In following article of 1231 words, tracing Tunda's career, he mentions about 1985 communal riot of Gujarat, in barely few words. A level headed writer, with peace of his country in mind, would have gone into both sides of the crime and come out with some peace-making, pacifying advice. On the contrary, he appears to incite and provoke one side, by exposing the other side in lurid details. Such people are guilty of sowing seeds of division among communities and are on the verge of inviting legal action for their paranoia poisoning the polity.

Ghulam Muhammed, Mumbai

<ghulammuhammed@gmail.com>

----- ----- -----

The Indian Express----- ----- -----

Generation of ‘avengers’ with Babri ’92 as motif

Abdul Karim Tunda after his arrest by Delhi police in 2013. (Source: File photo)

Abdul Karim Tunda after his arrest by Delhi police in 2013. (Source: File photo)

They buried Abdul Karim’s left hand under an acacia tree in the

scraggly forest just outside Tonk, wrapped in a plastic bag along with

the remains of the metal tube he’d been trying to turn into a bomb. It

was 1986, and just a few months earlier a district judge had ordered the

gates of the Babri Masjid opened to Hindu worshippers. In the years to

follow, much bloodshed would spread across India, with the Ram

Janambhoomi movement exploding every few months into communal killings.

From that day in Tonk on, Abdul Karim came to be known as “Tunda”, the cripple. He would lead his own war through, as a counterforce to the one unleashed by Hindutva groups.

In the weeks before December 6 this year, the anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Masjid, jihadist websites and Twitter accounts linked to a new generation of Indian radicals — of the Indian Mujahideen, now merged into al-Qaeda, of the Islamic State-linked Ansar al-Tauhid — invoked the memory of that event, and vowed vengeance.

The Babri Masjid remains the central motif for this generation of jihadists, just as it was for “Tunda”. His is a story that’s just starting to emerge from interrogation records and court documents as he awaits trial.

‘Defender’ of his faith

Born in 1941, on the eve of Independence, the son of a metal casting artisan who grew up in Gali Chhata Lal Mian in Delhi’s Daryaganj neighbourhood, Abdul Karim grew up in Pilkhuwa, Ghaziabad. Life was hard for the young Karim: forced to drop out of a missionary-run school at the age of 11, when his father died, he was put to work making cartwheels for his uncle. He began travelling across northern India, working as a metalworker, a cobbler, a carpenter, barber and bangle-maker.

In 1964, Karim married Zarina Yusuf, the daughter of his uncle’s brother. For the next two decades, he had a conventional lower-middle class life, working as a trader in dyed cloth, and bringing up three children, Imran, Rasheeda and Irfan.

The birth of the Ram Janambhoomi movement in 1984, though, generated intense communal strife. Karim responded by discovering religion: he turned to the neo-fundamentalist Ahl-e-Hadis sect for answers to the question why Muslims in India seemed to be passive victims in the face of oppression.

The search led him, in 1984, to Ahmedabad, where he began preaching Islam at a small seminary. He got married again, to Mumtaz Rahman, after his first wife refused to accompany him, and fathered a fourth child, Shahid.

He also lived an experience that would transform his worldview: witnessing the 1985 communal riots first hand. In his testimony to police, Karim described how Zafar Rahman, one of his in-laws, and seven other relatives had been burned alive. He talked of shops burned down, a mosque destroyed, and a police force that had joined mobs in attacking Muslims.

For weeks after the riots, Karim discussed the issue with an elderly local cleric, Maulvi Wali Muhammad. He segregated himself to study verses of the Qur’an on jihad. Karim emerged determined to defend his faith. He worked with a local vendor of fireworks to produce low-grade explosives using potash, sugar and sulphuric acid, packed into steel pipes.

His comrades

Karim wasn’t the only one with the same idea. Ever since he’d been a medical student, Jalees Ansari was later to tell police, he’d heard Hindus “branded us traitors and Pakistani agents”. From his clinic in a municipal hospital in Mumbai, Ansari read of riot after riot break out — in Moradabad, Meerut, Bhagalpur, and Bhiwandi. He saw what had happened in Bhiwandi first hand, as a volunteer distributing medical supplies.

In 1985, Ansari met the man who would give shape to his ideas — a former Maoist from Karimnagar in Andhra Pradesh, called Azam Ghauri, the fifth of 11 children from an impoverished family, and who too had discovered religion in the Ahl-e-Hadis. The men, along with Ansari, set up an anti-riot vigilante group, the Tanzim Islahul Muslimeen, or Organisation for the Correction of Muslims.

From 1989, prosecutors told Mumbai courts during Ansari’s eventual prosecution, the men began to put to use the bomb-making skills they learnt from Abdul Karim. Between September and October 1989, they planted low-grade explosives across Mumbai, following that up in 1990 with strikes at the Magh Mela in Allahabad, a bus stand in Pune, police premises in Bhiwandi and Mumbai — 11 in all.

In February 1992, months ahead of the Babri Masjid’s demolition, the group carried out strikes on the Shiv Sena’s premises in Mulund and Dadar. Then, after the demolition, they set off bombs at Kandivali railway station, on two commuter trains, and an express bound for Faizabad. In 1993, in the build-up to the first anniversary of the demolition, they bombed public spaces in Mumbai, and inter-city express trains.

The riots that followed the demolition, Ansari told police, convinced him they had no choice but to persist with violence.

“The Bombay police remained silent spectators when Muslims were being butchered by Shiv Sena activists,” he said. Justice B N Srikrishna’s judicial investigation of the 1992-93 violence in Mumbai came to the same conclusion.

Ansari was arrested; he completed a life sentence for the Mumbai bombings three years ago, but remains in jail as he is being tried for earlier attacks in Uttar Pradesh. He was born in 1952; his life could well end in prison.

Road to Pakistan

The Lashkar-e-Toiba first made contact with the Mumbai cell in December 1991, according to Ansari’s testimony to police, through Abdullah Shirazi, a Pakistan-origin jihadi who was being treated in Mumbai for bullet injuries sustained in Kashmir. Shirazi invited them to send recruits for training, but the plan went nowhere. In 1993, though, Ghauri and Karim separately made their way to Pakistan to obtain training and resources.

Later that year, Karim held the first of a series of meetings with Lashkar chief Hafiz Saeed, seeking help, as he put it in one interview with police, for suffering Muslims in India. Saeed offered him an opportunity to train at a Lashkar-run camp in Afghanistan’s Kunar. The by-now-portly Karim, though, returned halfway.

In August 1994, Karim moved to Pakistan — now an honoured guest of the Lashkar. The Lashkar set up a full India wing, commanded by Azam Cheema, which dispatched Salim Junaid, a Lashkar veteran, to set up an undercover cell in Hyderabad. He would die in an encounter with police — as would Ghauri, who came back to found his own group, the Indian Muslim Muhammadi Mujahideen.

Karim’s relationship with Saeed eventually deteriorated over battles for control of the Indian jihad. He publicly complained that the Lashkar leader had embezzled Rs 5 crore raised for jihad. The spat led to a run-in with the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate, who investigated Karim on suspicion of being an Indian agent. Karim retired, and set up property and perfume businesses. Arrested last year, now 73 and ailing, he could be heading for the second burial of his life in Tihar.

His ideas, though, fuel a new generation, forged in the crucible of the 2002 violence in Gujarat. This new generation includes men such as Feroze Abdul Latif Ghaswala, who, like Abdul Karim, had relatives slaughtered during the violence.

From that day in Tonk on, Abdul Karim came to be known as “Tunda”, the cripple. He would lead his own war through, as a counterforce to the one unleashed by Hindutva groups.

In the weeks before December 6 this year, the anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Masjid, jihadist websites and Twitter accounts linked to a new generation of Indian radicals — of the Indian Mujahideen, now merged into al-Qaeda, of the Islamic State-linked Ansar al-Tauhid — invoked the memory of that event, and vowed vengeance.

The Babri Masjid remains the central motif for this generation of jihadists, just as it was for “Tunda”. His is a story that’s just starting to emerge from interrogation records and court documents as he awaits trial.

‘Defender’ of his faith

Born in 1941, on the eve of Independence, the son of a metal casting artisan who grew up in Gali Chhata Lal Mian in Delhi’s Daryaganj neighbourhood, Abdul Karim grew up in Pilkhuwa, Ghaziabad. Life was hard for the young Karim: forced to drop out of a missionary-run school at the age of 11, when his father died, he was put to work making cartwheels for his uncle. He began travelling across northern India, working as a metalworker, a cobbler, a carpenter, barber and bangle-maker.

In 1964, Karim married Zarina Yusuf, the daughter of his uncle’s brother. For the next two decades, he had a conventional lower-middle class life, working as a trader in dyed cloth, and bringing up three children, Imran, Rasheeda and Irfan.

The birth of the Ram Janambhoomi movement in 1984, though, generated intense communal strife. Karim responded by discovering religion: he turned to the neo-fundamentalist Ahl-e-Hadis sect for answers to the question why Muslims in India seemed to be passive victims in the face of oppression.

The search led him, in 1984, to Ahmedabad, where he began preaching Islam at a small seminary. He got married again, to Mumtaz Rahman, after his first wife refused to accompany him, and fathered a fourth child, Shahid.

He also lived an experience that would transform his worldview: witnessing the 1985 communal riots first hand. In his testimony to police, Karim described how Zafar Rahman, one of his in-laws, and seven other relatives had been burned alive. He talked of shops burned down, a mosque destroyed, and a police force that had joined mobs in attacking Muslims.

For weeks after the riots, Karim discussed the issue with an elderly local cleric, Maulvi Wali Muhammad. He segregated himself to study verses of the Qur’an on jihad. Karim emerged determined to defend his faith. He worked with a local vendor of fireworks to produce low-grade explosives using potash, sugar and sulphuric acid, packed into steel pipes.

His comrades

Karim wasn’t the only one with the same idea. Ever since he’d been a medical student, Jalees Ansari was later to tell police, he’d heard Hindus “branded us traitors and Pakistani agents”. From his clinic in a municipal hospital in Mumbai, Ansari read of riot after riot break out — in Moradabad, Meerut, Bhagalpur, and Bhiwandi. He saw what had happened in Bhiwandi first hand, as a volunteer distributing medical supplies.

In 1985, Ansari met the man who would give shape to his ideas — a former Maoist from Karimnagar in Andhra Pradesh, called Azam Ghauri, the fifth of 11 children from an impoverished family, and who too had discovered religion in the Ahl-e-Hadis. The men, along with Ansari, set up an anti-riot vigilante group, the Tanzim Islahul Muslimeen, or Organisation for the Correction of Muslims.

From 1989, prosecutors told Mumbai courts during Ansari’s eventual prosecution, the men began to put to use the bomb-making skills they learnt from Abdul Karim. Between September and October 1989, they planted low-grade explosives across Mumbai, following that up in 1990 with strikes at the Magh Mela in Allahabad, a bus stand in Pune, police premises in Bhiwandi and Mumbai — 11 in all.

In February 1992, months ahead of the Babri Masjid’s demolition, the group carried out strikes on the Shiv Sena’s premises in Mulund and Dadar. Then, after the demolition, they set off bombs at Kandivali railway station, on two commuter trains, and an express bound for Faizabad. In 1993, in the build-up to the first anniversary of the demolition, they bombed public spaces in Mumbai, and inter-city express trains.

The riots that followed the demolition, Ansari told police, convinced him they had no choice but to persist with violence.

“The Bombay police remained silent spectators when Muslims were being butchered by Shiv Sena activists,” he said. Justice B N Srikrishna’s judicial investigation of the 1992-93 violence in Mumbai came to the same conclusion.

Ansari was arrested; he completed a life sentence for the Mumbai bombings three years ago, but remains in jail as he is being tried for earlier attacks in Uttar Pradesh. He was born in 1952; his life could well end in prison.

Road to Pakistan

The Lashkar-e-Toiba first made contact with the Mumbai cell in December 1991, according to Ansari’s testimony to police, through Abdullah Shirazi, a Pakistan-origin jihadi who was being treated in Mumbai for bullet injuries sustained in Kashmir. Shirazi invited them to send recruits for training, but the plan went nowhere. In 1993, though, Ghauri and Karim separately made their way to Pakistan to obtain training and resources.

Later that year, Karim held the first of a series of meetings with Lashkar chief Hafiz Saeed, seeking help, as he put it in one interview with police, for suffering Muslims in India. Saeed offered him an opportunity to train at a Lashkar-run camp in Afghanistan’s Kunar. The by-now-portly Karim, though, returned halfway.

In August 1994, Karim moved to Pakistan — now an honoured guest of the Lashkar. The Lashkar set up a full India wing, commanded by Azam Cheema, which dispatched Salim Junaid, a Lashkar veteran, to set up an undercover cell in Hyderabad. He would die in an encounter with police — as would Ghauri, who came back to found his own group, the Indian Muslim Muhammadi Mujahideen.

Karim’s relationship with Saeed eventually deteriorated over battles for control of the Indian jihad. He publicly complained that the Lashkar leader had embezzled Rs 5 crore raised for jihad. The spat led to a run-in with the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate, who investigated Karim on suspicion of being an Indian agent. Karim retired, and set up property and perfume businesses. Arrested last year, now 73 and ailing, he could be heading for the second burial of his life in Tihar.

His ideas, though, fuel a new generation, forged in the crucible of the 2002 violence in Gujarat. This new generation includes men such as Feroze Abdul Latif Ghaswala, who, like Abdul Karim, had relatives slaughtered during the violence.

http://indianexpress.com/

Words that sparked the ideas

Written by Praveen Swami

| New Delhi |

Posted: December 16, 2014 12:40 am

He’s almost unknown outside the sprawl of closed-in lanes that

run through Saidabad —once home to Hyderabad’s elite, now a run-down

lower-middle-class ghetto. From his spartan room in the seminary he

runs, Abdul Aleem Islahi’s words, however, have fired the imagination of

many young Indian radicals. Breaking with the Jamaat-e-Islami for what

he saw as its accomodationist posture during the Ram Janambhoomi

movement, he inspired many of the young radicals who set up the Indian

Mujahideen. He has never advocated violence — but his books are a map to

their minds.

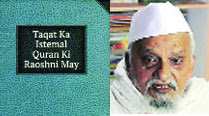

In Taqat ka istemal Quran ki Raoshni Main [‘The use of violence, in the light of the Qur’an’], an angry polemic, Islahi asserts that “war has been ordained against those who meet three conditions until they pay jizyah [a tax on religious minorities]: do not profess faith in God and Day of Judgment; do not accept as haram [forbidden] what God and his Prophet have declared haram; do not accept Islam as their religion”. It is, Islahi argues, “the duty of Muslims to struggle for the domination of Islam over false religions, and to subdue and subjugate infidels and polytheists”.

He concludes: “If the British nation can give in to the freedom fighters and a super power like Russia can surrender before the Afghans, why should we believe that Indian Muslims cannot succeed?”

In Nizam Khilafat-wa-Emirat, a disquisition on Islamic law on political power, Islahi argues that the practice of Islam cannot but be incomplete in a secular political order. Living under Muslim personal law “may be acceptable to God for the moment in view of our compulsion to live under a system of unbelief. However, we should not forget for a moment our goal of establishing an Islamic system of Khilafat and Emirate”.

He recruits the authority of the 13th-century theologian Taqi ad-Din Ahmad ibn Taymiyyah — pulled to centre stage by salafi-jihadist ideologues in the last century. Taymiyyah, he notes, “had issued the fatwa for those lands under the rule of infidel Tartars that the Muslims there should not remain contented eternally with this change”.

Thus, he goes on, “Indian Muslims had, and even today have, only two options. They should either form a Jamaat [a collective decision-making body for their affairs] or Emirate and fulfil their communal duties — or migrate. The third way of living permanently and happily under a rule by infidels and polytheists is not at all acceptable”.

The arguments Islahi made have acquired new resonance in recent months, as Islamic State’s forces have occupied growing swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria. In its August 25 issue, the Jamaat-e-Islami bi-weekly newspaper Dawat called on Indian Muslims to support Islamic State, arguing that this was a religious obligation.

In Taqat ka istemal Quran ki Raoshni Main [‘The use of violence, in the light of the Qur’an’], an angry polemic, Islahi asserts that “war has been ordained against those who meet three conditions until they pay jizyah [a tax on religious minorities]: do not profess faith in God and Day of Judgment; do not accept as haram [forbidden] what God and his Prophet have declared haram; do not accept Islam as their religion”. It is, Islahi argues, “the duty of Muslims to struggle for the domination of Islam over false religions, and to subdue and subjugate infidels and polytheists”.

He concludes: “If the British nation can give in to the freedom fighters and a super power like Russia can surrender before the Afghans, why should we believe that Indian Muslims cannot succeed?”

In Nizam Khilafat-wa-Emirat, a disquisition on Islamic law on political power, Islahi argues that the practice of Islam cannot but be incomplete in a secular political order. Living under Muslim personal law “may be acceptable to God for the moment in view of our compulsion to live under a system of unbelief. However, we should not forget for a moment our goal of establishing an Islamic system of Khilafat and Emirate”.

He recruits the authority of the 13th-century theologian Taqi ad-Din Ahmad ibn Taymiyyah — pulled to centre stage by salafi-jihadist ideologues in the last century. Taymiyyah, he notes, “had issued the fatwa for those lands under the rule of infidel Tartars that the Muslims there should not remain contented eternally with this change”.

Thus, he goes on, “Indian Muslims had, and even today have, only two options. They should either form a Jamaat [a collective decision-making body for their affairs] or Emirate and fulfil their communal duties — or migrate. The third way of living permanently and happily under a rule by infidels and polytheists is not at all acceptable”.

The arguments Islahi made have acquired new resonance in recent months, as Islamic State’s forces have occupied growing swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria. In its August 25 issue, the Jamaat-e-Islami bi-weekly newspaper Dawat called on Indian Muslims to support Islamic State, arguing that this was a religious obligation.

No comments:

Post a Comment