http://indianexpress.com/

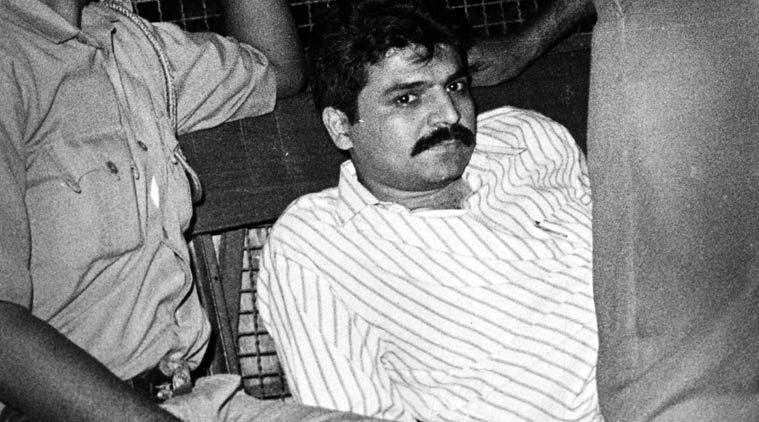

In this Sept. 18, 1993 photo, Yakub Memon is taken back to a jail in a police vehicle after he was allowed to visit his Mahim residence in Mumbai. (Source: Indian Express Archive)

The Indian Express

Yakub Memon’s ghost

Aftermath of his hanging puts at risk presumptive legitimacy of institutions that mediate social division.

Indian democracy will suffer from the shadow of the debate generated by Yakub Memon’s death sentence. The debate exposed barely concealed faultlines. It is a warning about the brittleness of the social fabric, which may be one accident away from cracking. It revealed just how much of our identities as citizens is constituted by sediments of resentment, suspicion and frustration. It is almost as if anger is all there is left to our moral agency. It opened up the legitimacy deficit of our institutions. Instead of transcending differences, these institutions are judged entirely on partisan lines. No one is willing to grant them a presumption of good faith.

Full disclosure: I oppose the death penalty on moral and practical grounds. I hope one day we will have a government that abolishes it. Even if the statute exists on the books, the state would do well to minimise its exercise. But many of my co-citizens think differently. In defending our respective positions, we may come to think of each other as deeply misguided or immoral. I also think it might be possible that we have a good faith disagreement on particular cases. In fact, one of the casualties of Indian democracy is that argumentative integrity and nuance are no longer possible. As Shekhar Gupta wisely pointed out, we often have to disguise our opposition to the death penalty under the technical, procedural and legal doubts of a particular case; conversely, the desire for a strong state often rides roughshod over details in particular cases. These risks are inevitable in a democracy. But what we saw this week was something more ominous.

First, there is an open legitimising of blood lust. Even if you believe Yakub Memon should have been hanged, the sensibility that accompanies that belief is important. For swathes of the media and civil society, the hanging was less about justice or concern for the victims. It was almost as if years of deep frustration, resentment and a sense of inadequacy about the state had morphed into an open mob mentality. Lawyers, doing their jobs defending Memon, were heckled. Many journalists displayed a lynching sensibility rather than professionally reporting the case. It is an open question how widely this sentiment is shared. But social media managed to create the postmodern equivalent of a medieval lynch mob, an almost cowardly but Talibanesque hounding of anyone who disagreed with the hanging. The calls for justice have become a pretext for aggression and faux patriotism. You wonder what insecurity and sickness lurks underneath, and what forms it will express itself in.

Second, institutions are not considered mediators of conflict or truth. They are weapons in a partisan battle. Of course, all institutions make mistakes, and this column has consistently defended the need to critique the courts. But we have reached a point where a specific disagreement immediately translates into questioning of the system as a whole. For those opposed to the hanging, several layers of appeal and many good faith protagonists count for nothing: They were simply window dressing for a justice system that is prejudiced and panders to the mob. For the right, justice is whatever is convenient to them. The courts are often wrong. But this wholescale conclusion is empirically untenable and dangerous. As Omair Ahmad’s study pointed out, it is hard to argue that the courts are systematically biased when it comes to acquittal rates across communities and cases. But it is also dangerous because it licences a kind of anarchy of judgement — we are all judges, whether we have encountered the evidence or not. To repeat, the courts make grievous mistakes; pointing those out is a right and duty. But taking away from them a presumptive legitimacy will leave us unprotected in every respect.

Third, the case has opened raw wounds, but in a way that is going to be politically explosive. Our state has an awful track record of prosecuting perpetrators of riots; and it has so far not shown credibility in its investigation of several terrorism cases. The silences over the Srikrishna Commission report, or 1984, or 2002, or Kashmiri Pandits, or whatever instance you want to pick, makes every legal case a case with subtext. Every case has to bear the weight of all our history with its omissions and commissions, prejudices and partisanship, unacknowledged crimes and un-redressed justice. It would be constructive if these failures were mobilised to think of how to create a better justice or investigative system. But our politics chokes off that discussion so thoroughly that it can now get articulated only in adversarial and pathological forms. It is all too easy to construct a narrative that there is political or communal partisanship in these investigations: Hindu outfits are given the benefit of the doubt; Muslim outfits the benefit of suspicion. Sometimes it is alleged vice versa, depending on the government. This is now a standard political narrative, and the language of legality, justice and terrorism has become the acceptable code through which communal politics is expressed. It will produce subterranean alienation in young people, and there are no political bridges across this divide.

This challenge is only going to deepen. Whatever the prime minister might say or believe, sections of the right that want to bait minorities are feeling emboldened. And their favourite tactic is to set up an ideological test for state institutions, whether in education or the police, and delegitimise them by making them appear partisan. This will create the conditions for a “takeover”. It is, therefore, doubly important not to play this game on their turf. This is why “shame on Indian judiciary” is a politically self-defeating response to the bloodcurdling “hang Yakub”. Impugning that presumptive legitimacy is exactly what the right wants.

Groups inside Pakistan sense that India’s vulnerability is not external. What can do India in is if a twisted sense of machismo leads to either greater communal polarisation or colossal geostrategic misjudgement. The right’s narrative, that India is a soft state, is understandable in some senses, particularly when it comes to the justice system. But it is false in other, deeper ways. The strength of the republic will be institutions with presumptive legitimacy, which can mediate conflict, and a political discourse that converts moderation into strength. The aftermath of Memon’s hanging has put both at risk.

The writer is president, Centre for Policy Research, Delhi and a contributing editor for ‘The Indian Express’.