BEEF NAMA

India is a democratic country. India is a secular country. The majority rules. The religions keep distance from State. Still a 3% Brahmin minority aided and abetted by a minuscule Jain minority, has been able to impose its religio-cultural diktats on the entire country, and that too for centuries --- in some form or other. BJP's rule in Maharashtra had brought in a very critical moment, when the ban of cow slaughter had turned into high criminal demonology. People are to be jailed for number of years, just for possession of beef. A situation much worse than the prohibition of liquor or drugs. However, the reaction to the new ban is now being realised by the rest of the majority in different lights. It is be realised that it is a draconian measures and imposes on personal constitutional rights of freedom of Indian citizens. Even though the measure has pointedly aimed as hitting at Muslims, the impact of the ban is developing into an gross anti-people measure. A gradual consensus is appearing to take hold of the liberals who are not communal and/or religious in strictest sense of the words and are ever vigilant to counter all fascist moves by the Saffron fanatics for their self-promotion as the very epitome of uber-nationals to finally grab India for their hundred year old ambition to change India into a exclusive preserve of their existentially disintegrating

Indian Express has come out with 3 important articles, that highlights how beef is ingrained into the lives of those that are not Brahmins or call themselves up-castes. And they are the discriminated majority that are bound to react and ask: where is the beef.

Ghulam Muhammed, Mumbai

---

Memories of Meals Past: For the Dalits in Maharashtra, the ban snaps their link to cheap protein

New Delhi | Published on:April 5, 2015 1:00 am

By Anjali Lukose and Alifiya Khan

Tiny prawns have replaced the succulent beef, but a craving for the mouth-watering “kaali dal aani beef curry” or black lentils with beef curry refuses to go away.

It’s been a month since the Ingles, who work at the fishing dock at Bhaucha Dhakka or ferry wharf in South Mumbai’s Carnac Bunder, tasted their mother’s signature dish. The ban on slaughter of bulls and bullocks in the state and the self-imposed ban on slaughter of water buffaloes by beef dealers meant that the Ingles could find no beef anywhere. This, despite living across one of Asia’s largest abattoirs in Deonar, central Mumbai.

A beef recipe that Lalita Ingle picked up from her grandmother is the family’s favourite. “Thodi kalimari, kuch garam masala. Uska correct mix mein hi beef ka mast taste aata hai (Some pepper, some garam masala. The correct mix is the secret to the yum beef curry),” says Lalita, who is in her mid-40s. “Marinate the meat properly and cook it well but not in excess oil and then mix it with dal and it tastes almost as good as when my aaji (grandmother) used to make it,” she says. Lalita, her husband and three children, all working at the docks, live in the Bhim Sevak Sangh Mohala, Deonar.

For 12 hours a day, seven days a week, 60-year-old Pune resident Suman Ratikar, a ragpicker by profession, goes house to house picking wet waste from dry waste with her bare hands, cleaning verandahs for an extra five rupees and often ends up having to lift soiled diapers. Two days a week, she keeps a fast, which she breaks with chapati and a dry gravy made of beef innards.

Both the Ingles and Ratikars are a part of a food culture that is as old as any other in India. In 2009, a team of researchers from the University of Pune embarked on a project to unearth the food memories of Dalits. “Yes, beef-eating is an intrinsic part of Dalit culture and has been a major source of protein for the community for ages. But it’s important to understand whether this was a choice or food economics that forced the community to eat beef. The basic idea was to untangle the caste, class and gender dynamics of the food we eat,” says Sangita Thosar, a teaching associate at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, and a Dalit. She was a part of the editorial team of Isn’t This Plate Indian? Dalit Histories and Memories of Food, the result of the project which was led by the late sociologist Sharmila Rege.

The aim of the project was not just to show how deprivation determined Dalit food habits, but also to explore the cuisine’s creativity, its ability to make the most of its frugality. For example, chunchuni is dried and salted beef which is stored sometimes for an entire year, and consumed when families have no money to buy vegetables. Kandawani is a dish made with only onions, with a similar philosophy: to be made when nothing else is available. “Rakti might sound gross to you but is quite nutritious. It is made of coagulated chunks of cattle blood. No part of the animal was wasted,” says Thosar, whose family is from Rohkal village in Osmanabad district’s Paranda Taluka, and who belongs to the Mahar community. Dalits possess their own distinct culinary traditions, she says, but they never figure in any cookbooks, “which only mention upper-caste recipes”.

The book acknowledges that food was central to the concept of untouchability as the Brahminical order first decided who would eat what, and later made it a mark of pure and impure status.

The probable history of why Dalits took to beef lies in the upper-caste Hindu’s aversion to meat as he began to afford a range of vegetables and dairy products. For Dalits, who couldn’t buy richer meats like chicken or mutton, beef remained a staple. “Often it would be the dried meat of dead and decaying cattle. One cooked liver or innards which came at one-third the price. These are fatty portions and require less oil to cook too. For a woman like Ratikar, who gets Rs 50 a day can only spend Rs 40 once in a week to buy beef innards, any other meat is unthinkable,” says Thosar.

The Ingles live in a mixed colony. Here, the mostly fisherfolk Dalit community cohabit with the Qureshi butchers and meat handlers working at the abattoir across the street. The Ingles would buy beef twice a week, mostly at a discounted rate, from their neighbours. While the market rates were Rs 140 a kg, the Ingles would get fresh beef from the abattoir at Rs 100 a kg.

“We bought beef, because it is tastier and relatively cheaper,” says Lalita, who sells fish at the docks. “Now, we bring home more prawns and Bombay Duck to compensate,” she says. More than the dish, the Ingles say, the grim mood at their neighbours’ makes them wish the ban would be repealed. “Chalo, in desperation, we can manage with dal-chawal also. But for our friends, it is a question of their livelihood,” says Sagar Ingle, Lalita’s 22-year-old son.

Thosar believes the ban on beef (except meat from water buffaloes) in Maharashtra will spell disaster for the community. “Imagine the chief protein source vanishes from your diet. Soon prices of water buffalo will go up too. Will they be able to afford it?” she says.

But April 1 was a special day for the Ingles. Their neighbours and close friends were back on duty at the abattoir. “It’s twice the excitement today. Our neighbours have got their jobs back and we will get beef tonight,” says Sagar, referring to the Qureshi community returning to their jobs, this time culling only water buffaloes. “Just yesterday, my father who cannot live without beef, planned to go to Mumbra. He heard they were selling beef there. Legal or illegal, my father did not care. That’s how much he misses it,” he says.

For one night, at least, the smell of beef curry would waft through this lane.

---

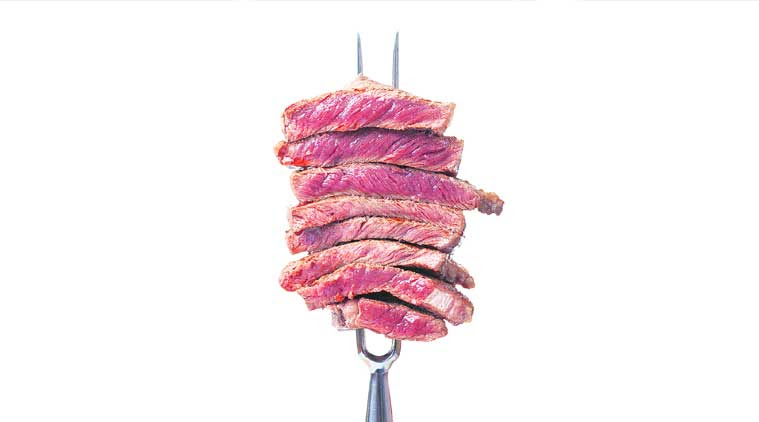

How not to waste your beef

Written by Adam Halliday | New Delhi | Updated: April 5, 2015 7:15 pm

Looking at the north-south expanse of Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, from a nearby ridge, Liansanga, 34, a community leader, pointed towards a hill-side meadow surrounded by trees and said, “When we were kids, that’s where we used to tether Christmas cows.” It is a custom in these parts for every congregation to save money through the year to buy at least a pig and a cow for the Christmas feast.

“A bunch of us would walk down from the neighbourhood every morning and feed it. It was always the responsibility of the kids to make sure the cow was fattened,” he remembered.

Pigs, on the other hand, are never given such treatment. They are simply bought from its owner and slaughtered near the sty it has always lived in.

It never has and may perhaps never equal the pride of place its wilder cousin, the bison, has in stature as meat, but beef is now more commonly consumed across the tribal, non-Hindu regions of the North-East because it is cheaper and more widely available.

For some tribes in Arunachal Pradesh, it is a lesser meat because while the bison is the meat of choice during celebratory festivals or marriages, beef is rather like chicken and mutton. For some Nagas, it is either a meat for the less wealthy (those who cannot afford to slaughter a pig for a festive family occasion offer guests beef) or sometimes a side-dish accompanying bison meat (when a bison is slaughtered for community feasts, a cow usually follows).

An old Naga saying goes that when male relatives travel to a distant village to look for and find a bison to slaughter for a girl’s wedding feast, the bison will travel on its own to where the wedding will take place. No such mythical intelligence is afforded to the cow, however, a pointer to where it stands on the pantheon of meats.

But nonetheless, beef is widely consumed, and no part of the cow’s body is wasted. Lean meat, tongue, brain, innards, legs, bone, marrow, and no, not even the tail.

The Mizos relish the lean meat when it is simply boiled in some amount of water with seasonings and salt. Most, by the way, swear by the soup’s Viagra-like properties. Sometimes, it is cut into strips and smoked. The Khasis add a larger range of vegetables such as potatoes, cabbage and onions to make stew of it, or mince it to turn out cutlets. Most Nagas like lean meat smoked in thin strips and shredded to accompany chutneys of fermented soya-bean and local herbs.

“We don’t fry our food. Beef has it’s own juice, we add ginger, garlic, chilli powder or fresh green chilli, according to our preference, put it on medium heat and let it cook,” said Aketoli Zhimomi, proprietor of Dimapur’s Ethnic Table restaurant and one of Nagaland’s most famous chefs.

Arunachal Pradesh’s Tani group of tribes smoke it over the hearth fire in large chunks or stuff them into bamboo placed near the flame, bringing it to slow tenderness. “We eat everything from the stomach to the brain to the tongue. Usually they are all cooked inside bamboo, where we place ginger, garlic and some native leafy begetable and we roast it near the fire in the hearth. We call the leaf we use to line the inside of the bamboo akum. We add a little bit of water, and then we slow cook it. So it’s roasting and steaming at the same time,” says Moyir Riba, of the Gallo tribe, one among the Tani group of tribes.

Among the tribes that inhabit the central hills of Arunachal Pradesh, beef innards freshly extracted from their bamboo ovens offer conviviality, for it is more often than not an accompaniment to apong, local beer made from rice or maize, a mildly sweet drink that slowly but surely affects the head.

The head, of course, offers yet another delicacy. The head of a cow, that is. Particularly the brain.

Nagas mostly make incisions all over this organ so a paste of ginger-garlic, chilli and salt seeps into its inner sanctums. The whole is then wrapped in a plantain leaf and stuffed under the warm ashes of a hearth. On top, a wood fire is built. After this, it is dry fried in bits on a pan, then add bamboo-shoot and Raja Mircha (considered the world’s hottest chilli), serving it as a sort of chutney.

Surely some part of the animal must not be consumed, like the bone? “The bone?” asks Zhimomi, bewildered for a moment before recovering with a giggle, “Oh, we love to chew our bones. And the marrow is what we really fight over at home.”

---

Medium, Not Rare

Written by Premankur Biswas | New Delhi | Published on:April 5, 2015 1:00 am

In Rayaz Beef King restaurant, chunks of beef sizzle in a silken red gravy, gargantuan pots of beef biryani are emptied in a matter of hours and moist beef rolls are expertly assembled by the dozens. Sheikh Rayaz, the proprietor of the 40-year-old establishment, insists that business has been “always good”. Even on a sleepy weekday afternoon, the two-storied establishment at the mouth of Prince Anwar Shah Road in South Kolkata is buzzing with customers. Rabi Nandi, 54, a government bus driver, is finishing his meal of beef curry and rice when he decides to join our conversation. “I am a Hindu and I have been a regular customer here for more than 20 years. No one in my family likes having beef but I love the taste. Who is the government to dictate my eating habits?” asks Nandi.

Mumbai might be a city without beef but Kolkata certainly celebrates the flavourful meat. Or does it? Most Muslim-owned biriyani joints in the city sport the “No-beef” tag to “draw in more customers”. Even at the celebrated Nizams, the signature beef roll is no longer on the menu. “We have customers from all communities visiting us, we have to cater to their needs as well. That’s why we did away with beef items from our menu. Even a lot of Muslims don’t like having beef outside their homes,” says Anwar Hussain, a waiter at Nizams.

Most of the places that serve beef actually serve buffalo meat because it’s cheaper and cow slaughter is still frowned upon by most people. “There are a few places where you can get cow meat but they tend to be low-end eateries,” says Poorna Banerjee, a food blogger.

Rayaz Beef King is one such place. Here, plywood tables and wooden benches are the seating arrangement, most of the restaurant spills over to the pavement and none of the items on the menu cross the Rs 50 mark. But that doesn’t deter the customers. “We even have foreigners visiting our restaurant. In fact, one British gentleman was so impressed that he suggested that we name the restaurant Beef King after the famous chain in England. That’s how the restaurant got its name,” says Rayaz.

Even though the search for beef in Kolkata does not drag you into the entrails of a black market, a whiff of disapproval clings to it. “Of course, there is the religious issue but there is also a class thing. Even a number of rich Muslims don’t have beef because it’s considered a poor man’s meat,” says Banerjee.

It’s in the outskirts of the city, in places like Baruipur and Sonarpur, where you will find beef in abundance. “There, people would rather pay Rs 70 for a plate of beef biryani than Rs 100 for a plate of chicken biryani,” says Banerjee. At Asma Hotel, a 35-year-old institution adjacent to the bustling Baruipur station, the pricing is the USP. The flavourful beef biryani has customers making two-hour-long drives for a meal. “Most of our customers are daily labourers. We try to serve them good food for a reasonable price. You would be surprised to find that 80 per cent of our customers are Hindu,” says Masood Ali.

At Park Street and its surrounds, beef items are widely available. The beef steak at Olypub, one of the most popular watering holes of the city, runs on its reputation rather than anything else. “I find it rather chewy but I order it nonetheless. There is an element of glamour in ordering beef steak at Olypub,” says Arkadeep Sarkar, a music teacher with Ashok Hall High School. Sarkar, a Hindu Bengali, knows his parents don’t approve but they have never really stopped him. “As long as I don’t cook it at home. It’s like me consuming alcohol, they pretend that it never happens,” says Sarkar.